How do you know if your brand is 'on brand'?

The first step is measuring what’s in people’s minds. But this isn’t so easy.

This guest post has been generously contributed by Ethan Decker, PhD., President of Applied Brand Science, opens in new tab

“Is this work on brand?”

We’ve all heard it before: the question of whether your Instagram post is “on brand”. Or your photo shoot. Or your ad. Or your radio spot.

Usually, it's tested by checking with someone inside the company who knows the brand well. Maybe the founder. Or someone in design who knows the Pantone colors for the logo too. Maybe someone in marketing when it comes to a message or an activation. Once in a while, people refer to a brand document of some sort: a brand book, brand guidelines, a brand onion, or my thing, a one-page brand DNA.

But here’s the thing: you really can’t know if something is “on brand” or not, until you ask the people for whom it’ll matter the most: your buyers and your prospects. Do they think that pop-up store was on brand? Do they think that your latest collab is on brand?

This takes us into an entirely different realm of how to figure out if your work is “on brand” or not. And that’s the realm of understanding what your brand is like — not on the shelf, and not on the screen, but between people’s ears.

But here’s the thing: figuring out what’s going on inside people’s minds is hard. Like, really harrrrrd. Harder than tracking media expenditures. Harder than tracking Meta stats on a dashboard. Harder than tracking scanner data. So marketers often avoid it.

Don’t. That’s a big mistake.

Obviously, this is where a great tools like Tracksuit comes in. But before getting into brand tracking, let’s review the most common mistakes marketers make when trying to understand what people think, feel, or know about a brand.

The top 3 mistakes when probing people’s minds

1. Only talking with brand fans

Many marketers start with the easiest source of info: their fans.

First, they read what their fans say on reviews. It’s a good place to start, really, even if it’s an odd sample; you usually know nothing about their age, location, reliability, etc. You only know they are the kind of people who leave reviews.

Next, marketers ask their subscribers or past buyers some questions. This is often something like a survey that goes out to everyone who’s registered for them or purchased their products in the past 6 months. This, too, is really valuable info. But again, it’s a bit of an unknown sample. And most respondents are a) people who like them enough to subscribe, and b) interested enough to answer some questions or fill out a survey. So they’re usually fans.

Talking to your fans is important. You can learn a lot from them. But if you ONLY talk to your fans, you’re ignoring three vital groups:

- The folks who tried your brand once or twice & ditched you. It’s vital to know why they ditched you. You’d better talk to these folks.

- The folks who buy you but aren’t fans. They’re light buyers. They think you’re fine. Or they see you as maybe one of a few good options. Or they’re happy buying you once a year or whatnot. It’s key to talk to them because they probably outnumber your fans by a factor of 5X–10X. Srsly.

- Your prospects: people in the category, but who haven’t tried you yet. And this group can be vital because — news flash — virtually all your future growth will come from people not buying your brand today.

SO: you need to talk to those other folks too. Learn what they think & feel about your brand. Otherwise you’re just hearing from people who loooooove you and think you’re so amaaaaaazing — and comprise maybe 6% of your sales.

The cleanest way to do this is to recruit a nationally-representative sample of people who tend to buy your category. You need to consider how often or how long ago they bought your category. (E.g., if it’s dish soap, is it ok if it’s been 2 years since they bought it? Probably not. But if it’s a comfy reclining chair, is it ok if they simply own the brand & bought it 12 years ago? Maybe.)

Tracksuit, f’rinstance, has great sampling protocols and tools to help ensure you’re getting the right sample of respondents. They also have lovely tools for breaking down your audience: age, gender, income, region, etc. Good stuff.

Then you need to consider if they’re the ones using the product or if they’re the primary shopper for it. F’rinstance, in maybe a third of US households, the female head of household does the primary grocery shopping for the fam. She doesn’t use her son’s Old Spice deodorant. She doesn’t use her husband’s socks. And she doesn’t eat her dog’s food. But she buys it all, and often that means she’s the decision-maker, even though she’s not the user.

2. Asking too much about behavior

There’s a well-known gap between what we say and what we do. And there are at least two reasons for this gap. First, it’s just hard to remember things. Most people can barely remember what they had for breakfast yesterday. I certainly can’t recall how many times I’ve changed my toothbrush in the past 12 months with any accuracy. Nor can I remember how many miles I put on my car even this month.

Second, we have what I like to call “wishful recall.” We say we floss regularly, but our teeth beg to differ. We say we eat healthy, but really we are just putting defrosted peas in our mac & cheese. We say we are loyal to Levis, but, well, there’s that nice selvedge denim pair of Gustins in our closet too. Amazingly, these errors in recall seem always to be in our favor. Funny that.

So you must proceed with great care when asking people directly about their behavior. It almost seems counterintuitive; wouldn’t the easiest way to find out how much bourbon people drink be to just ask them? Easy, yes. Accurate? Maybe not. And be careful, because as my statistics professor Ed Bedrick famously and frequently boomed at us with great foreboding, “Bad data takes you confidently in the wrong direction!”

SO: if you’re just asking people to recall their behavior, keep your questions general, and try to make realistic demands on their paltry memories. Or if you can, measure actual behavior in other ways, and use your direct questions to ask about their perceptions, their feelings, and their thoughts. (Super bonus points if you ‘validate’ your survey questions with actual behavioral data. F’rinstance, compare your toothbrush survey with actual purchase data, perhaps, to see what the say-vs-do gap actually is.)

Tracksuit doesn’t ask unrealistic behavioral questions. In fact, one of their main survey questions is super simple & clean: have you used this brand?

3. Asking people to be entirely logical

I love my Maratac automatic watch. Why? I could give you some beautiful reasons: the domed sapphire crystal, the reliable Miyota 9015 movement, the super luminova on the hour marks, the great price point, etc. But really, if I were honest? I’d tell you it’s just a clean, sharp-looking watch, and it makes me happy to wear it. Also, I love it that it has no brand name on it, so watch guys (it’s almost always guys) have to ask me who makes it once they notice it. (Such a dorky power move.)

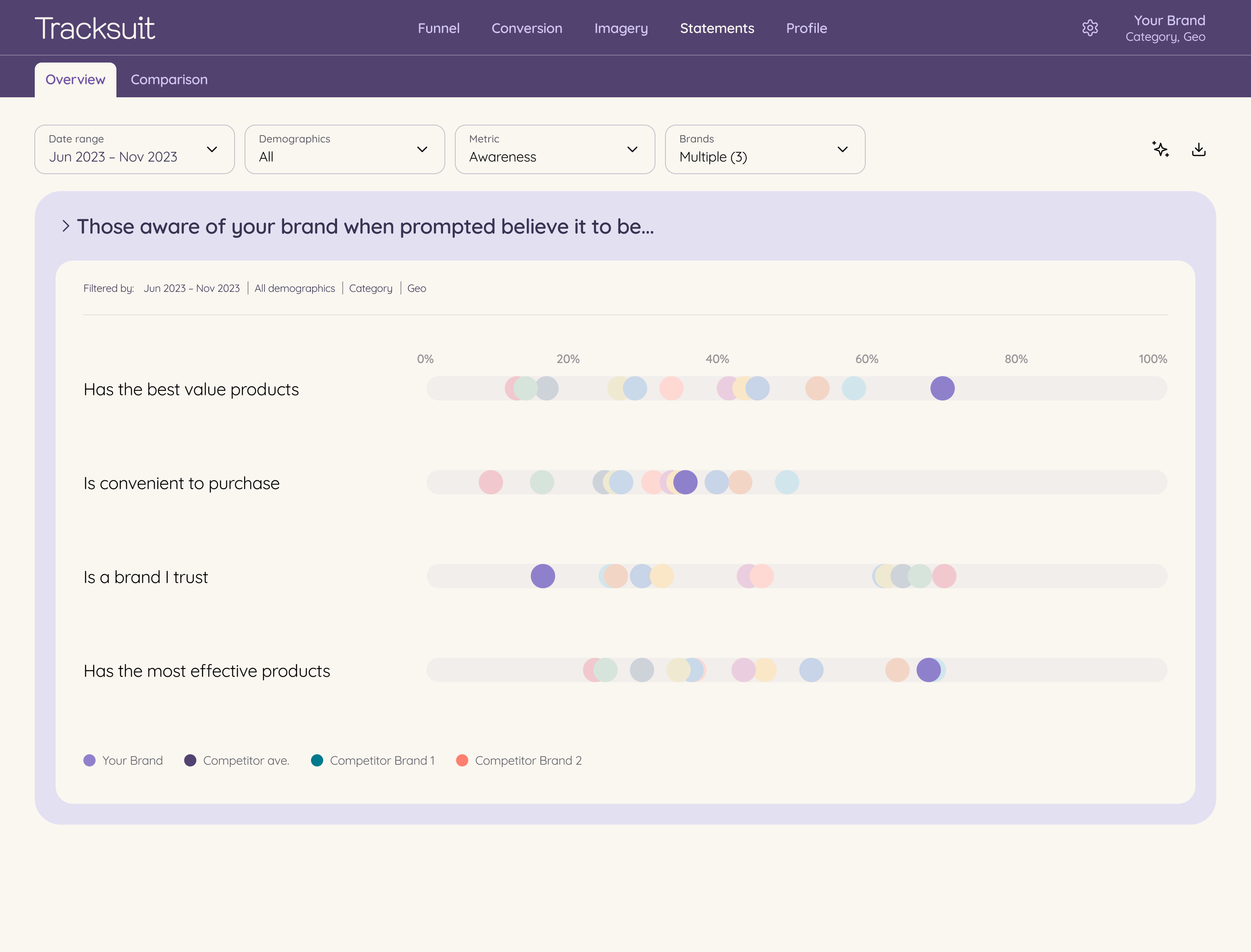

But if all you ask in your survey is about reliability, “value for price”, and whether it’s a brand I trust, you won’t get all that juicy good stuff that sounds a little crazy. You’ll just get my rational-sounding answers to your rational-sounding questions.

SO: cut way back on the logical questions that lead the witness. And instead, leave white space for people to express their less-than-logical selves. (Besides, lately, AI is a huge help in analyzing that unstructured qualitative data.)

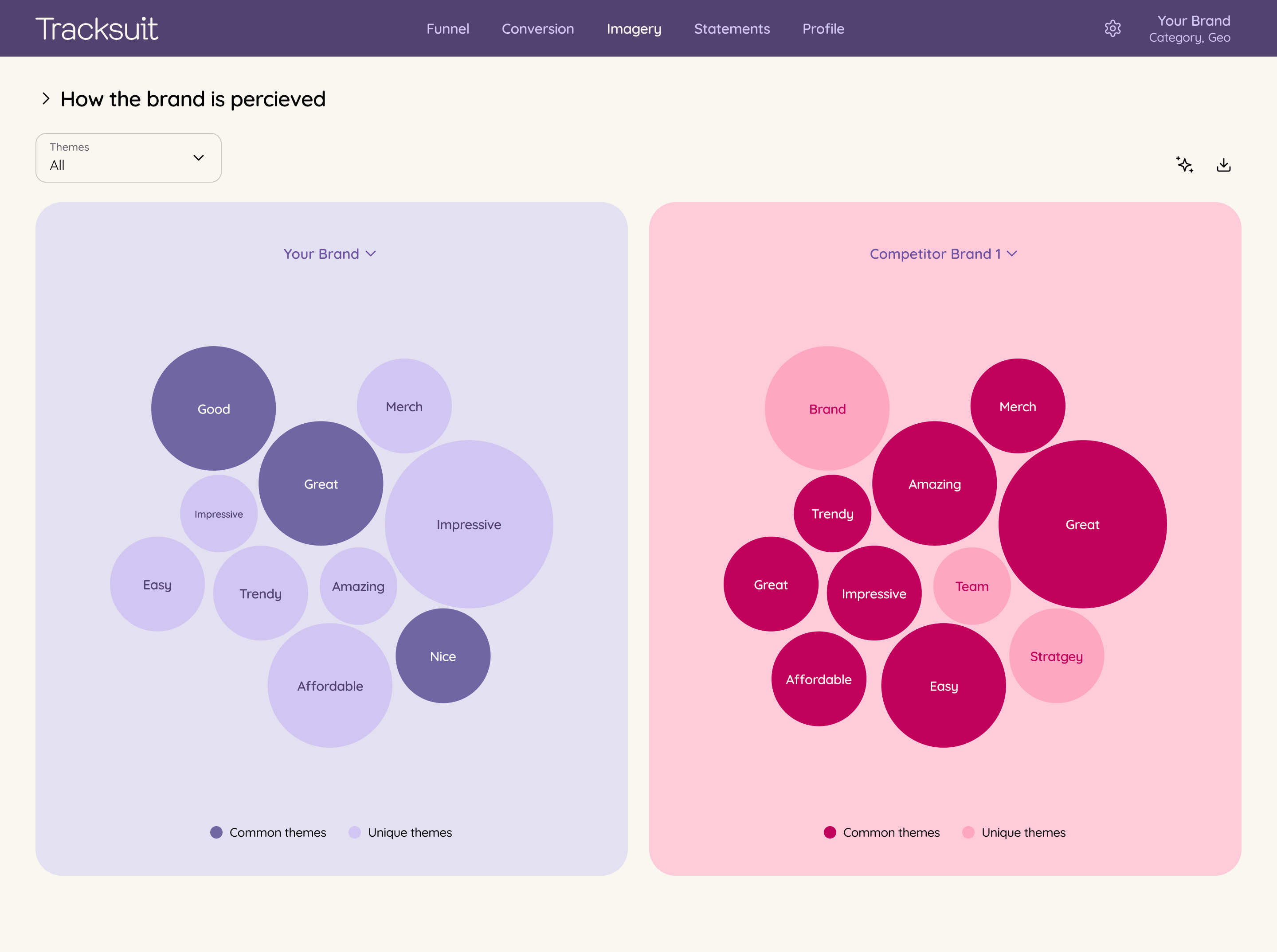

Tracksuit does just this. Depending on the category, they ask a couple of questions about basic things (innovative, premium, trustworthy). Then they ask a very open-ended question about what comes to mind for each brand. I love that. It’s a wide-open space that allows all kinds of weirdness in.

And finally, they show the summary of the verbatims in a fun bubble chart called the Imagery view. You can toggle between themes common to brands and themes unique to brands too.

Find out if your brand is on brand

Okay. Those are 3 of the biggest mistakes marketers make when surveying people. Fortunately a platform like Tracksuit doesn’t make them. Which means you’ve got better data, a better view on your brand, and a better sense of the category.

There are other steps to finding out if your brand is on brand. (Tune in next time for more about those.) And, yes, spoiler alert: Tracksuit is part of them too.

But getting the fundamentals right is, well, fundamental to the task. As Ed Bedrick used to say (though he didn’t boom this one): “Research starts and ends with GIGO: Garbage In, Garbage Out.” (Thanks, Ed.) So you really need to ensure you start with good quality, farm-grown, pasture-raised, hormone-free data.

Author bio: Cross a scientist with an improv comic, and make him do marketing for 20 years for some of the world’s great brands, and you end up with something like Ethan Decker. Through his company Applied Brand Science, Ethan teaches business leaders the “new science” of how people really shop, how ads really work, and how brands really grow. He makes complex ideas simple, useful, and sticky. Ethan was voted “Best session at SXSW” in 2023, has 12,000 followers on LinkedIn, and his TEDx talk is among the top 1% most-viewed TEDx talks of all time.